Jacobsen Gulch Priority Area

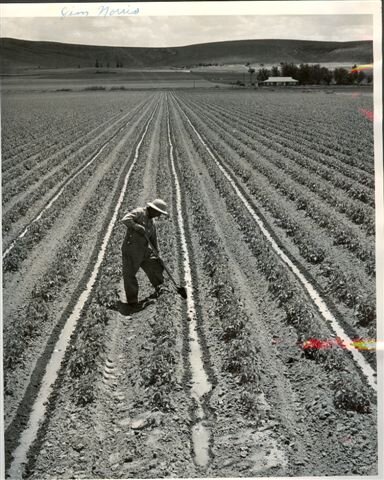

At the beginning of the Great Depression, government and private entities were enticing settlers to come to the Vale, Oregon area. The Vale-Owyhee Government Projects Land Settlement Association, organized in 1929, coordinated the settlement process. Settlement grew steadily because of the association's activity and the effectiveness of the irrigation system built by Bureau of Reclamation. Settlement grew as the canal and lateral system expanded. In 1930, there were 4,142 acres opened. There are now roughly 256,000 irrigated acres in northern Malheur County. Bureau of Reclamation designed the irrigation system to store water in several reservoirs, (the Owyhee Dam was completed in 1932, and the Agency Dam in 1935) , deliver water to farms by dirt canals, and have the farmers use furrow irrigation to water crops. The tailwater from the fields was captured by a series of canals, which allowed other farmers to reuse the water before it left the irrigation districts. This system was efficient in its time, as it used the force of gravity and enables the reuse of water.

However, this style of irrigation has contributed to top-soil loss, water quality and quantity issues and long-term productivity problems. Water quality in the Malheur Basin is a top natural resource priority for landowners, irrigation districts, NRCS, Malheur SWCD, OSU Extension and the Malheur Watershed Council. Collaborative restoration efforts and on-farm project implementation, which target management of irrigation induced erosion and tailwater return flows; have been highly effective approaches to water quality improvement in the Malheur Basin over the past 20 years. Irrigation infrastructure conversions are a preferred management approach for reducing sediment and weed seed transport and increasing irrigation efficiency. Irrigation system conversions can be costly and, in some cases, cost prohibitive to landowners and irrigation districts. Collaboration with multiple partners and funding sources can help to make irrigation system transformations cost-effective and make significant impacts to improving water quality.

Over the past several years, Malheur Basin partners, including the Watershed Council, NRCS and Malheur Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD), in cooperation with private landowners have been prioritizing water quality improvement areas to focus on-farm sprinkler conversion and other management practices. The priority area approach concentrates funding and technical assistance into smaller geographies within the Basin based on the following criteria: landowner cooperation, existing water quality information, and expected achievable water quality benefits through implementation. This approach has proven to be successful in prior implementation water quality improvement priority areas.

The Jacobsen Gulch Water Quality Improvement area is an example of this focused effort and collaboration in action. “A few things brought it to the forefront as a priority area; First and foremost, landowner interest and willingness to participate,” says Lynn Larsen, District Conservationist with the Malheur County NRCS office.

A completed pivot from one of the projects in the Priority Area

Steve Bochenek was one of the early project participants and helped coordinate the initial effort. He had a settling pond at the base of his furrow irrigation field. “Every few years, I would have to go in and haul the dirt out,” said Steve, “You don’t realize how much top soil you are losing unless you capture it and let it settle through the year, then you realize ‘Wow, tons and tons of topsoil is being lost off every year’.” He expressed interest in converting to pivot irrigation to help combat erosion, improve water efficiency, and save labor.

A meeting was held on site to gauge landowner participation. “It was really critical to have landowners lead the way,” says Lynn. “We visited about the potential project area, what their goals and aspirations were, and what kind of projects they wanted to do. The irrigation district was there and talked about what they would like to do. It just developed from there.”

Once projects were approved and funded, the Council worked in close coordination with NRCS and the irrigation district to ensure a smooth transition to implementation. “What we have found over the years of doing these irrigation projects is that we are good at doing portions but not all. And so having a partner come in, we are able to complement each other’s efforts,” says Lynn. Dealing with the many various aspects of completing just one project, such as a pivot installation, can be complex. “It went unbelievably smooth; I had no problems. It does take some time, which is understandable with the studies and engineering. You can’t get in a hurry,” says Steve. Each partner may be taking on different portions of the project but constant communication throughout the process ensures a smooth transition to implementation. Steve’s project, along with others in the Jacobsen Gulch priority area, have been implemented on time, on budget, and with all requirements met.

Water quality data has been collected before, during and after implementation and that data has not been analyzed yet. “It’s too early in the process to see the results but I can speak to other areas where we have done similar projects and the improvement in water quality is overwhelming. It’s really doing exactly what we had hoped it would do,” says Lynn.

This irrigation season was the first use of the pivot for Steve. “There is quite a learning curve. There is a lot work involved in converting from furrow irrigation to pivot irrigation, more than I had anticipated.” But he added that he was very pleased with the results and the irrigation itself. “As far as the actual irrigating, going and pushing a button is much easier than changing gated pipe three times a day; there is a huge labor savings.”

“In some cases, it allows the farm to transform how they grow their crops. It really enhances their ability to not only grow crops but enhance their bottom line,” says Lynn. “It is really cool to be involved in projects where when you walk away, not only are the natural resources better off but the producers themselves are too.”